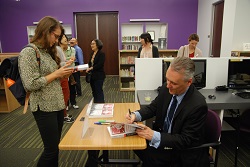

UCLA modern Japanese history professor William Marotti brought his academic research on a fascinating but little-known artistic period to a broader audience when he visited the Japan Foundation, Los Angeles to give the lecture "Art, Protest, Revolution: Avant-Garde Madness in 1960s Japan." Based on material from his new book Money, Trains, and Guillotines: Art and Revolution in 1960s Japan, Marotti's lecture covered the small but radical art movements that sprouted up in early-60s Tokyo, a time of discontent in the wake of January 1960's Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, also known as the "ANPO treaty." At that time, said Marotti, the antics of "dissenters, eccentrics, and oddballs" shed light on Japanese society's "hidden politics" by producing not pure nonsense, but "alternative forms of sense."

UCLA modern Japanese history professor William Marotti brought his academic research on a fascinating but little-known artistic period to a broader audience when he visited the Japan Foundation, Los Angeles to give the lecture "Art, Protest, Revolution: Avant-Garde Madness in 1960s Japan." Based on material from his new book Money, Trains, and Guillotines: Art and Revolution in 1960s Japan, Marotti's lecture covered the small but radical art movements that sprouted up in early-60s Tokyo, a time of discontent in the wake of January 1960's Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, also known as the "ANPO treaty." At that time, said Marotti, the antics of "dissenters, eccentrics, and oddballs" shed light on Japanese society's "hidden politics" by producing not pure nonsense, but "alternative forms of sense."

Examining the early 1960s in Japan, Marotti found several predecessors of political art movements that would become well-known later in the decade in places like Europe, North America, and elsewhere in Asia. He sees in this early era of protest the beginnings of modern Japanese "cultural attunement" through works of "playful junk art," "objects put under radical scrutiny," and "happenings" before the very concept found its official artistic definition, all of which "returned eventfulness and potential" to Japan's "troublingly quiescent" postwar life. He illustrated this idea with stories and showed us images of such works by Nakanishi Natsuyuki, who built striking, often funny forms from bones, clock parts, watches, eggshells, and eyeglass lenses, and who even attempted performance art on Tokyo's busy Yamanote train line with fellow political prankster Takamatsu Jirō.

Marotti also went into great detail about the images of thousand-yen notes produced by artist Akasegawa Genpei, which irked the Japanese government enough to haul him into court on an obscenity charge. The p rofessor's lecture presented Genpei's project as a rich representation of all that ultimately became important about the activities of the early-60s Tokyo avant-garde, which took sometimes serious risks to develop, effectively, the experimental prototypes of the "later, greater protests" against the ill-serving governments of the late 60s and 70s. Both "Art, Protest, Revolution" and Money, Trains and Guillotines come as the culmination of over twenty years of research, which all began, suitably enough, with a grant from the Japan Foundation.

rofessor's lecture presented Genpei's project as a rich representation of all that ultimately became important about the activities of the early-60s Tokyo avant-garde, which took sometimes serious risks to develop, effectively, the experimental prototypes of the "later, greater protests" against the ill-serving governments of the late 60s and 70s. Both "Art, Protest, Revolution" and Money, Trains and Guillotines come as the culmination of over twenty years of research, which all began, suitably enough, with a grant from the Japan Foundation.

The universality and global characteristics of Japanese art that so pique the interest of the Western art world are not all to be found in mere Japonism. Recently, a number of exhibitions featuring Japanese art of the 1960s and 1970s in particular have been held on both coasts of the United States. In Professor Marotti's masterpiece Money, Trains, and Guillotines: Art and Revolution in 1960s Japan, he describes Genpei Akasegawa and other little-known unorthodox artists of the Avant-Garde movement that developed as Japan realized its independence in the chaotic postwar period. As Japan went through the growing pains of becoming one of the world's most developed industrial and economic powers, how did these artists bear witness to this massive upheaval in their society? Join us in experiencing the earth-shaking madness brought forth by the artists of 1960s Tokyo.

The universality and global characteristics of Japanese art that so pique the interest of the Western art world are not all to be found in mere Japonism. Recently, a number of exhibitions featuring Japanese art of the 1960s and 1970s in particular have been held on both coasts of the United States. In Professor Marotti's masterpiece Money, Trains, and Guillotines: Art and Revolution in 1960s Japan, he describes Genpei Akasegawa and other little-known unorthodox artists of the Avant-Garde movement that developed as Japan realized its independence in the chaotic postwar period. As Japan went through the growing pains of becoming one of the world's most developed industrial and economic powers, how did these artists bear witness to this massive upheaval in their society? Join us in experiencing the earth-shaking madness brought forth by the artists of 1960s Tokyo.

Professor William Marotti is an Associate Professor of History at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and is Chair of the East Asian Studies M.A. Interdepartmental Degree Program.

Professor William Marotti is an Associate Professor of History at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and is Chair of the East Asian Studies M.A. Interdepartmental Degree Program.

Professor Marotti teaches modern Japanese history with an emphasis on everyday life and cultural-historical issues.